A quick snapshot of the March 2023 National Population data release today shows that population growth continues at its furious pace.

- Australia recorded a record net overseas migration (NOM) inflow of 152,000 in March quarter 2023. This in turn took annual NOM to 454,000 in the year to March 2023, which is a massive 50% above the previous record of around 300,000 back in 2009. Quarterly NOM has now surpassed 100,000 in four of the past five quarters, after never having been above 100,000 prior.

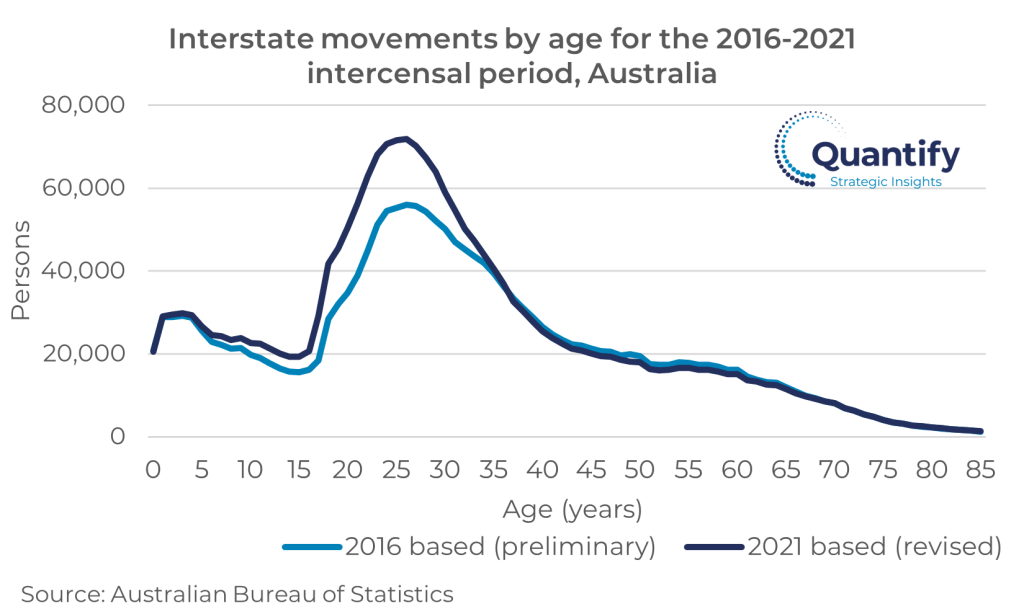

- Total interstate movements continue to moderate, down by 8% on March 2022 to 94,000, which is also below the immediate pre-COVID levels. Extremely tight rental markets could be reducing housing options and having an impact on population mobility. Queensland and Western Australia continue to experience net inflows. The other states and territories all experienced a net interstate outflow in the quarter, with the outflows from New South Wales and Victoria having eased somewhat over the past couple of years.

- Births registered in March quarter 2023 have continued at the lower level that emerged after the post-COVID bounce during calendar 2021. Cost of living pressures could potentially see births take another leg down over the next year or two.

- Meanwhile, deaths have continued at the higher level that emerged in 2022 and remain above the five-year average. The higher deaths could play out for some time due to the limited preventative care that is likely to have taken place through COVID lockdowns.

Australia’s population grew by 563,000 in the year to March 2023 and national population growth is running above 500,000 per annum for the first time in history. Assuming NOM ends above 450,000 in FY2023 and Treasury’s forecast for NOM of 315,000 remains on target for FY2024, Australia will have completed its post-COVID population ‘catch up’ in the space of a mere two-and-a-half years, with population at June 2024 back where it was expected to be prior to onset of the COVID pandemic. The speed of this reversal has left the housing market flat-footed an unable to respond quickly enough with the consequences now being seen in housing rental markets.

For further insight into what this means for population growth and housing markets nationally and across the states, contact Angie Zigomanis at angie.zigomanis@quantifysi.com.au or Rob Burgess at rob.burgess@quantifysi.com.au