The 2021 Census outputs provide fascinating insights into the impact of COVID on the Australian population, particularly the rise of single person households.

Key highlights are as follows:

- Compared to the 2016 Census, there was a noticeable reduction in the prevalence of group households and couples with children. Conversely, there was a corresponding increase in lone person households (up from 24.5% to 25.6%), reflecting those in share households and adult children in couple family households striking out on their own in search of space.

- After increasing from 2.56 to 2.59 persons per household (in private dwellings) over 2011 to 2016, household sizes fell to an average 2.54 in 2021. While this does not seem like much, it represents around 192,000 extra dwellings being occupied across the population or soaking up around a year’s supply.

- Vacant dwellings decreased from 11.2% of the total private dwelling stock in 2016 to 10.1% in 2021. Some of this will reflect the rise in occupied dwellings due to smaller household sizes. However, COVID lockdowns also meant fewer people were out of their homes on Census night. In addition, 632,700 people were out of their homes and temporarily overseas in 2016, compared to only 37,000 in 2021.

The rise in occupied dwellings has been reflected in extremely tight rental markets. SQM Research reports vacancy rates fell nationally from 2.6% in April 2020 at the onset of the pandemic, to 1.0% in May 2022 – the second lowest figure it has recorded.

Figure 1: Census housing dynamics, Australia

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing

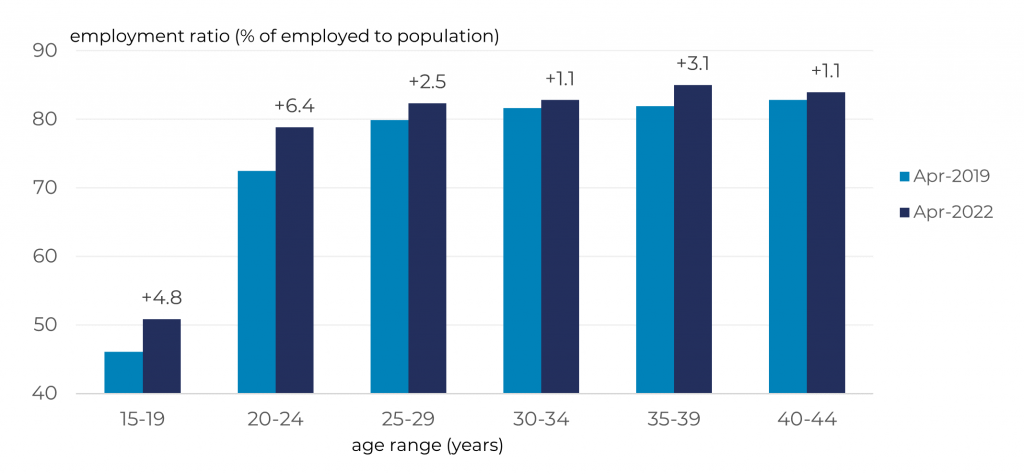

It should be noted that other contributing factors besides COVID are also at play here. After all, if people are able to move out of the family home or share accommodation into their own place, why weren’t they doing it before COVID? Analysts have missed the impact of Australia’s strong employment market. The percentage of people employed is now higher than pre-COVID. The largest increase is for those aged 15-19 and 20-24 years old (Figure 2), who also have the highest incidence of share housing and living with parents.

Moreover. the total number of hours worked has grown at a greater rate than jobs. So, in addition to more of the population being in work, they are (on average) working more hours and therefore earning a higher income. This in turn has increased the financial capacity to form separate households.

Figure 2: Share of population employed by age, Australia

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics – Labour Force

So, are smaller households here to stay?

In the short term, perhaps. Rents are already rising, and a recovering net overseas migration will place upward pressure on rents and reduce rental affordability. Tight labour markets mean younger households should have some initial capacity to absorb rent increases. In addition, the increased ability to work from home allows renters to compromise on location, rather than household size. Middle ring suburbs, where vacancy rates have typically been highest and rents still weak, will provide an affordability outlet as rents rise.

In the longer term, perhaps not. Those at the margins would be expected to retreat to affordable options such as share housing or moving back to live with mum and dad. As population growth accelerates, the ability to shoehorn households into the available dwelling stock will become increasingly difficult and rents will rise more significantly. As they did through the COVID pandemic, households will adjust the other way and the incidence of share housing and children remaining in the family home is likely to eventually revert to previous norms.

If you would like to know more about changes in household composition and the impact on your business, feel free to reach out to one of Quantify’s principals at info@quantifysi.com.au.